Last week we concluded our post with a visit to the Chateau d’Amboise. Our bikes are parked in convenient bike racks on the main square of Amboise, near the entrance to the chateau. Leaving the chateau we walk up the rue Victor Hugo 400 m to the Clos-Lucé, a small chateau where Leonardo da Vinci spent his last three years. At the end of our visit there we will return to our bikes and cycle the 30 km back to Tours.

Clos-Lucé was built in the late 15th century of tufa stone and pink brick. This is a rare and lovely combination; it is also to be seen at Louis XI’s chateau in Tours, Le Plessis-les-Tours, a place we will visit on a subsequent bike ride.

The property was acquired by King Charles VIII in 1490 as a refuge for his wife, Anne de Bretagne, a very devout woman. He added an oratory at the chateau for her, where she came frequently to pray. A fresco in the oratory is titled the Virgin of Light (Virgo Lucis); it is thought that the Lucé in the chateau’s name comes from Lucis, a reference to the painting, which may have been done by da Vinci’s loyal assistant Francesco Melzi. Clos means an enclosed place, and in this case a quiet, protected place.

The chateau, which has been the property of the Saint Bris family since 1855, was opened to the public in 1954.[1] From the chateau terrace, there is a splendid view of the Chateau d’Amboise, which Leonardo must have enjoyed.

The French kings of the 16th century knew Italy through warfare. From 1494 to 1559, Charles VIII, Louis XII, François I, and Henry II waged a series of wars which involved invasions of northern Italy. The wars were often based on competition among France, Spain, and Venice for control over the various city states of Italy. These excursions allowed the French kings and the nobles fighting with them to see the marvels of the Italian Renaissance.

In 1499 Louis XII’s troops marched through Lombardy and took Milan, where he visited the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan and saw Leonardo’s fresco of 1498, The Last Supper, painted on the wall of a large room which became the refectory. He was so taken by the work that he asked if it could be detached and transported back to France. His request was perforce denied (frescos don’t travel well), but copies of the painting soon appeared in noble houses in France.

François I invaded Italy and captured Milan in October 1515. The king met with Pope Leo X in Bologna; Leonardo, who was present at the meeting, received a commission to make a mechanical lion for the French king. A year later, at the invitation of François I, Leonardo was in France; he had been living a difficult life in Italy with few commissions. He arrived at Clos-Lucé during the first few months of 1516. François I was out of town that day on state business, but he certainly would have joined Leonardo at the first possible moment.

François I had been well educated in the wonders of the Italian Renaissance and during his reign sought to bring the new artistic styles to France. He would have known Leonardo as one of the leading lights of the Renaissance. What better way for the King to show his leadership in cultural affairs than to have Leonardo live next to his court in Amboise? Leonardo was given Clos-Lucé as a residence and a substantial annual pension, so that he could work without financial worries.

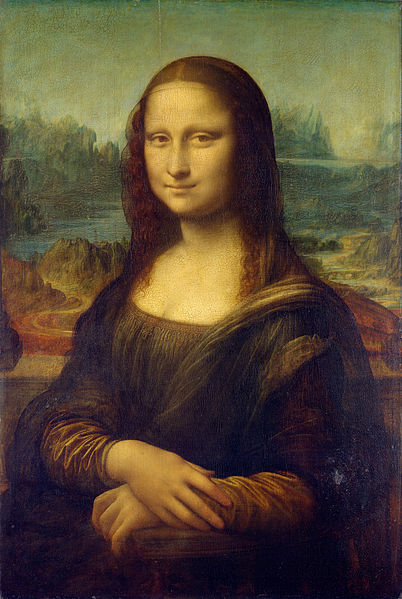

The many sides of Leonardo’s genius are on display at the Clos-Lucé: the artist, the philosopher, the creator of magical events, the scientist, the engineer. The artist is celebrated with reproductions of his paintings, including the Mona Lisa (La Joconde in French), which hangs proudly in the Renaissance Great Hall of the chateau.

The philosopher appears in the many pithy Leonardo sayings that are hung throughout the chateau, like the one below.

4. Dr. Al Salmoni of The University of Western Ontario at the Clos-Lucé during the 2010 Western student bike trip, bike helmet in hand.

Translating the French (“La rigueur vient toujours à bout de l’obstacle“) involves at least two options, depending on how you treat rigueur. Rigeur often refers to precision of thought, and thus da Vinci may be making a statement about science and intellectual work in general; in that case the translation might be “Precise thinking overcomes every obstacle.” A more general interpretation of rigueur would lead to the translation which dominates the many websites devoted to da Vinci quotes: “Every obstacle yields to stern resolve.” As a career professor and lifelong runner, Dr. Salmoni can endorse both interpretations, as his smile in the photograph indicates.

Leonardo had established a reputation in Italy as a creator of magical events, often held at night, using innovative lighting, costumes and backgrounds of his own design, and employing his technical skill with machines created for a specific party. His first such event at Clos-Lucé was on May 3, 1517, to celebrate the baptism of the King’s first son, and the marriage of the King’s niece. Leonardo was a master of theatrical drama and surprise, and the King and his guests loved his shows.

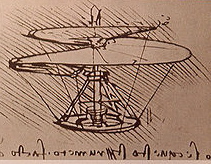

Leonardo the scientist and engineer appears in the many drawings displayed from Leonardo’s notebooks, including the one below.

Apart from his paintings, it is the sketches in his notebooks which provide the most tangible evidence today of Leonardo’s genuis. The notebooks consisted of some 13,000 loose pages which have wound up in museums across Europe. The pages show models for machines and scientific inventions, and sketches for paintings, along with grocery lists and household budgets.

The pages were not published during Leonardo’s lifetime and virtually all remained unpublished for centuries; thus for most of his proposed inventions, the eventual machines were designed, built, and run by people who had no knowledge of Leonardo’s drawings. A great many of the pages were gathered, translated, and published for the first time in 1883 by Jean-Paul Richter, a German art historien. The Notebooks, as assembled by Richter, are now on the internet; Richter’s Preface is fascinating, as are Leonardo’s notes and sketches. [2]

Happily, of Leonardo the scientist and engineer, at Clos-Lucé we can see more than the sketches. Years ago the IBM Corporation built actual models of forty inventions shown in the sketches, using materials available in Leonardo’s time. These are on display in the basement of the chateau. One of the models is a cross-section of a boat propelled by two side paddle wheels, driven by cranks which would presumably be turned by hand. Two large flywheels would steady the motion.

Like so many of Leonardo’s inventions this one had to wait until the appropriate source of power was available.

The park outside the chateau celebrates Leonardo’s love of nature; he strolled in this park 500 years ago. The small Amasse river flows through the park on its way to the Loire; the river has been cleverly redirected to allow for a series of bridges and other structures which illustrate Leonardo’s designs: a two-level bridge, a swinging bridge for military use, a mill operated with gears he sketched, an Archimedes screw. On the edge of a small pond is a larger model of the paddle wheel boat.

While the IBM models in the chateau basement are fragile and cannot be touched, many of those in the park are made to be operated by hand, much to the delight of children, and indeed some adults. There are two cranks for turning the paddles on the boat in the park.

A model of the “helicopter” sketch in photograph 3-5 is to be found down a grassy slope from the chateau entrance.

In the middle of the six supports is a vertical shaft. In theory, if you could turn that shaft fast enough, the wings of the structure on top could lift it up into the air. Just as with the paddle boat, the needed power was not available in de Vinci’s time. Commercial paddle boats would await the steam engine and the early 19th century. Helicopters, which needed the internal combusion engine, became operational in the 1930s and 1940s.

While celebrating Leonardo’s achievements, the Clos-Lucé site also allows us to contemplate the mystery of this extraordinary man. Why so few completed paintings by one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance? Why so many projects, artistic and engineering, begun but not finished? Why no major publication during his lifetime on his philosophy, his science, or his engineering? And why, despite these shortcomings, do we hold him up as the ultimate Renaissance man?

This mystery is at the heart of a recent biography by Sophie Chauveau, Léonard de Vinci (Gallimard, 2008), who traces the life of a genuis who is constantly seeking new challenges and working most of the time in difficult circumstances. She cites the British author and art historien Kenneth Clark, that each generation must reinterpret this extraordinary person.[3] It is no accident that in his fabulously successful fictional story, The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown gives a central role to Leonardo and his paintings and sketches, and even puts his name in the book’s title. The da Vinci legend continues to fascinate us.

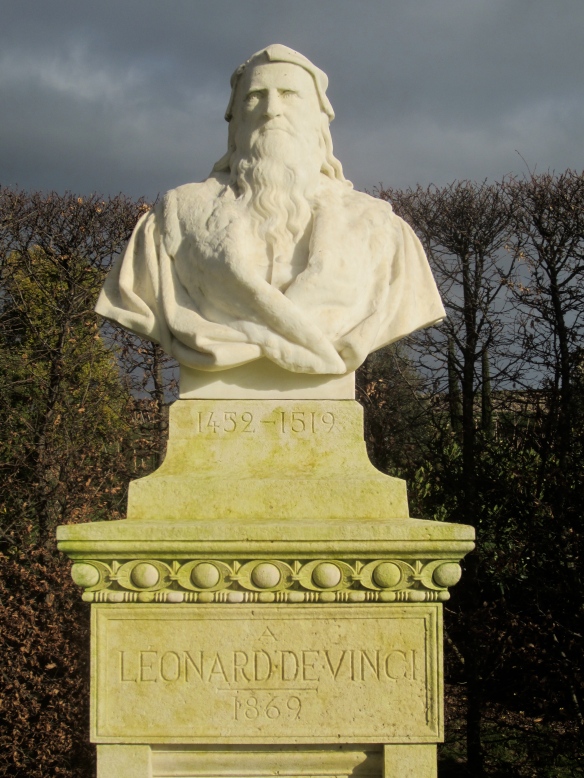

Leonardo died on May 2, 1519 at Clos-Lucé. A popular myth, that he died in the arms of Francois I, is the subject of a painting by the great 19th century artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. A reproduction of the painting hangs next to his bed in Leonardo’s bedroom at Clos-Lucé.

In all likelihood, however, the King missed Leonardo’s death at Clos-Lucé just as he had missed his arrival. According to Chauveau, on that day Francois I was baptizing his second son at Saint-Germain-en-Laye west of Paris, over 200 km away. Part of the mystery of Leonardo is the resting place of his final remains. At his request he was buried inside the Chateau d’Amboise, in the Saint-Florentin church. The church was badly damaged during the Revolution, and taken down by order of Napoleon I in 1808. A bust of Leonardo was later erected on the site of the church.

So far, so good, but now the tale gets twisted. One story has it that in the 1860s Leonardo’s bones were found on this site, and transferred to the Saint-Hubert chapel, where they still lie under the stone on the floor in the photograph below.

The plaque on the wall in the photograph concludes with the following sentence on Leonardo’s remains: “His presumed remains found during excavations undertaken in 1863 were transferred to this chapel.” The use of “presumed” (restes présumés) shows the appropriate doubt. The official Chateau pamphlet drops the doubts and tells the visitor flat out that the Saint-Hubert Chapel is indeed the grave of Leonardo.

Yet doubts remain. Why were the bones discovered so long after the razing of the original chapel in 1808? One source suggests that the 1863 excavations were done by the French State.[4] If true, this could certainly increase our scepticism, because the head of state at that time was Emperor Napoleon III, who was desperate to justify his undemocratic regime with popular causes. Why not associate himself with Leonardo, just as François I had done three centuries earlier? The bust in Figure 3-10 is dated 1869, just a year before Napoleon III had to flee France.

Sophie Chauveau is convinced the whole “discovered bones” story is a myth and that his final resting place is just one more Leonardo mystery. Indeed, she believes that the mystery of da Vinci’s life was one that he himself cultivated. She ends her book as follows [5]:

“So Leonardo has played his last trick.

There is no gravestone real or figurative for the greatest artist of the Renaissance. Nothing? Not the smallest trace. A man who scattered traces of himself all his life, as if to cover his footsteps, sees his wishes literally granted in his death.

He rests nowhere.

The legend can continue.

And it continues.”

[1] The current head of the family, Gonzague Saint Bris, is a remarkable man–journalist, novelist, biographer, romantic, shameless self-promoter, loved or hated by all in the literary elite. Jean-Louis Gouraud has written a wonderful portrait of Saint Bris, “Les Éléphants Sont-Ils Romantiques?” (La revue, no 6, octobre 2010), which is displayed on Saint-Bris’ website, http://www.gonzaguesaintbris.com.

[2] http://www.sacred-texts.com/aor/dv/index.htm

[3] Chauveau, p. 9: “qu’a chaque génération cet étonnant personnage devait être réinterprété.”

[4] http://www.amboise.com.

[5] Chauveau, pp. 263-264:

“Ainsi le dernier tour de Léonard est joué.

Aucune sépulture réelle ni figurée n’existe pour le plus grand artiste de la Renaissance. Rien? Pas la moindre trace. Lui qui n’a cessé d’en semer de son vivant, comme pour mieux brouiller les pistes, voit ses voeux littéralement exaucés dans sa mort.

Il ne repose nulle part.

La légende peut continuer.

Et elle continue.”

Photographs 3, 5, and 9 are from the Wikipedia Commons, commons.wikimedia.org. All other photographs were taken by the author.